|

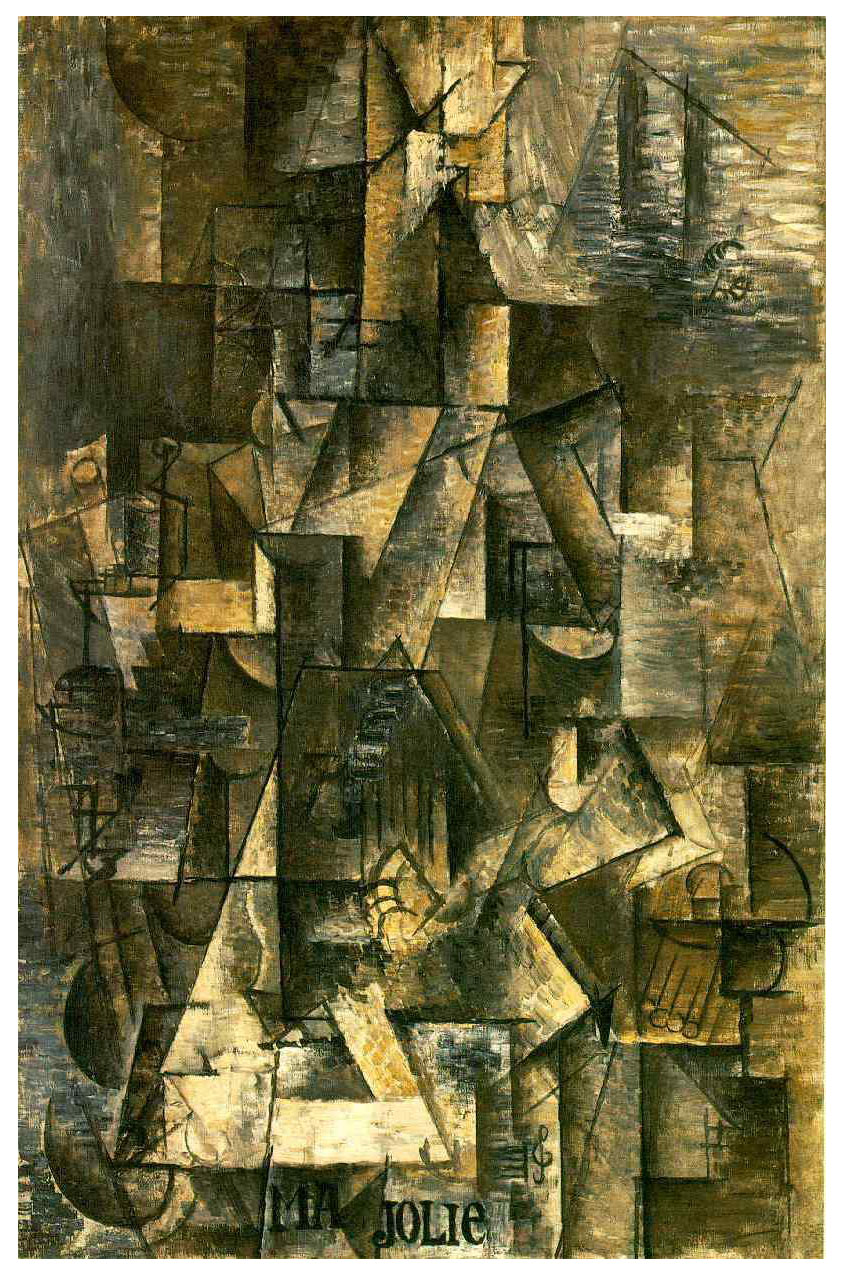

| Andre Masson, Automatic Drawing, 1924 |

Automatism is known as the passive

phase of Surrealism, whereas paranoia-criticism, or paranoiac-critical, is

known as the active method. With the active method, Dali achieves the symptoms

of paranoia through simulation of various mental diseases and then utilizes

this altered state of mind to create his unconscious images (Gordon, 235). Dali

believed this method was the most pure and accurate way to tap into the

unconscious. In his mind, the active process would trump automatism as the

primary method of Surrealists because, “…it was the systematic character of

paranoia, the way in which it was itself an interpretation of reality, rather

than subject to interpretation, that made it superior to automatism and dream

accounts that were all too subject to rationalization after the fact, and thus

recuperation” (Harris, 731). Dali believed the reality one interprets in a

paranoid state of mind is a pure representation of their unconscious; it was

not subject to rationalization and thus freed ones mind from rational control

to reach the surreal.

|

| Salvador Dali, Le grand paranoiaque, 1936 |

In addition to painting images

realistically, Dali also employed the tactic of double images. He believed the

ability to portray and see a double image epitomized the paranoiac. He argued

that the work paranoia is able to perform on already existing images is the

proof of its active character and opposed the invention of new images in the

passive, automatic method (Harris, 732). Many of Dali’s paintings contain

double images, including his famous Visage

Paranoiaque, Dormeuse, cheval, lion invisibles, and Le grand paranoiaque.

The multiple interpretations present in these images are a

result of ones paranoia. Dali makes sure that no single reading dominates; he

creates “…a multiple image which can never settle into a single interpretation”

(Harris, 734); this to Dali is a pictorial representation of the unconscious.

Although some scholars argue that there can be no such thing as an unconscious

painting since it is so planned out and formulated, Dali argues that such

elements as double-images are directly tapping into the unconscious.

|

| Salvador Dali, Visage Paranoiaque, 1935 |

|

| Salvador Dali, Dormeuse, cheval, lion invisibles, 1930 |

Although surrealists may argue in favor of a certain artistic method, the aim of both the passive and active methods is the same. They both

try to deliberately tap into the unconscious, which the Surrealists consider to

be “the prime source of artistic inspiration” (Gordon, 230). The Surrealist

movement is a manifestation of the self-reflective questions that have plagued,

and continue to puzzle humankind. We ask: what is really going on inside our minds? Scholars in all fields from

psychology and neurobiology to sociologists and artists tackle this question;

everyone believes they have the closest thing to the answer. Dali was a victim

to this conceited pattern and believed his paranoid critical method was the

true way to tap into the unconscious, the prime source of artistic expression.

Whether he was correct in his theory or not, he created works that resonated

with people around the world and fueled an artists movement that renounced the previous norms of aesthetics and morals.

Gauss, Charles E. "The Theoretical Backgrounds of Surrealism." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 2.8 (1943): 37-44. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2012. <http://www.students.sbc.edu/evans06/Gauss%20reading.pdf>.

Gordan, Donald A. "Experimental Psychology and Modern Painting." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 9.3 (1951): 227-43. Wiley-Blackwell. JSTOR. Web. 15 Nov. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/425884 .>.

Harris, Steven. "Beware of Domestic Objects: Vocation and Equivocation in 1936." Art History 24.5 (2001): 725-57. Wiley. Web. 15 Nov. 2012. <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/1467-8365.00293/asset/1467-8365.00293.pdf?v=1&t=ha2w6ebt&s=c717d060f1d8e7f2100c7ea2771882f3aebe5cb8>.